WRITING

Richard Saunders, Chairman

Philip Awashish, Commissioner

COVER, DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

gordongroup marketing + communications

PRINTING

Gilmore

TRANSLATION

George Guanish (Naskapi)

Mary Mokoush (Naskapi)

C.I.L.F.O. (French)

Louise Blacksmith (Cree)

PHOTOGRAPHY

Philip Awashish

Gaston Cooper

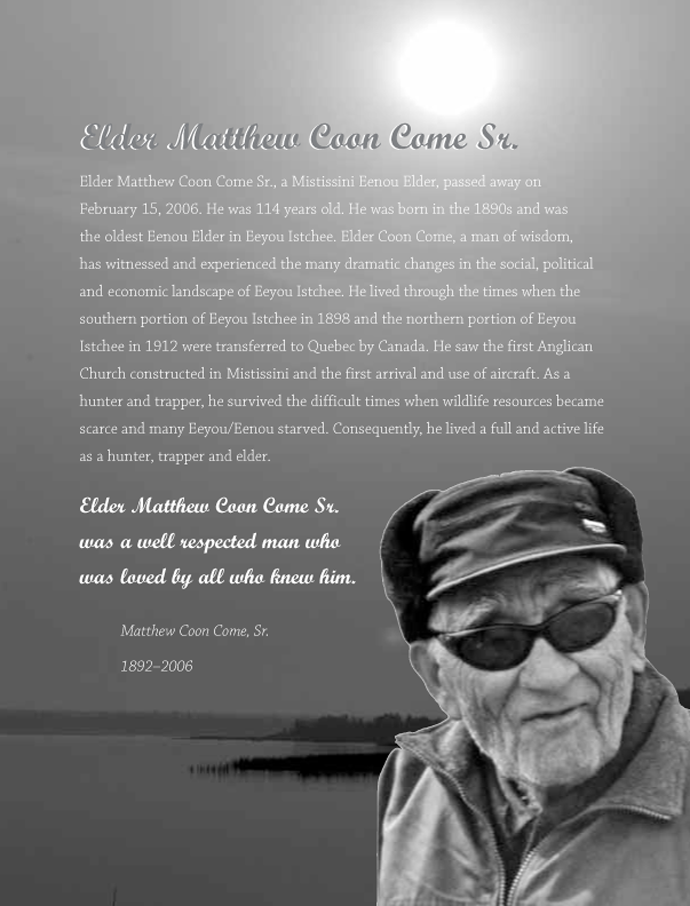

Bjorn Olson (Matthew Coon Come, Sr.)

CONTACT US

Cree-Naskapi Commission

222 Queen Street, Suite 305

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5V9

telephone: 613 234-4288

facsimile: 613 234-8102

toll-free: 1 888 236-6603

WEB SITE

www.creenaskapicommission.net

IV

|

On our 20th anniversary of the operation’s of the Cree-Naskapi Commission, the Commissioners wish to thank the representatives and officials of the Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee), local Governments of the Cree and Naskapi Nations and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development for the presentations at the Special Implementation Hearings which were held in preparation by the Commission for the present biennial report. These presentations are essential for an informative report on the issues and concerns of the Eeyou Nations and the Government of Canada. The Commissioners are also grateful to the staff of the Commission. The work and contributions of Brian Shawana, Gloria Dedam and Charlotte Kitchen have made this report possible. |

June 30, 2006

Honourable Jim Prentice, PC, MP

Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development

Parliament Buildings

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H4

Dear Minister,

We are pleased to submit herewith the tenth biennial Report of the Cree-Naskapi Commission pursuant to section 171.(1) of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act.

The report is based upon hearings and other consultations and discussions at which the Cree and Naskapi and their governments as well as the Government of Canada presented their views, concerns and suggestions relating to the implementation of the Act. We have also reviewed written input from your department and various other sources. Finally, we have also taken into account the broader issues raised in specific representations which we have received since our 2004 Report.

We look forward to meeting with you and your officials to discuss how our findings and recommendations might be followed up to the advantage of all concerned. After the Report has been tabled in Parliament, we shall be discussing it with the Cree and the Naskapi as well as with other interested parties.

Respectfully,

Cree-Naskapi Commission

Richard Saunders |

Robert Kanatewat |

Philip Awashish |

| Philip Awashish Commissioner

Philip Awashish was one of the principal Cree negotiators for the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee in the negotiations leading to the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. For 20 years, he has served the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee, in various capacities, such as Executive Chief and Vice-Chairman of the Grand Council of the Crees (of Quebec) and the Cree Regional Authority and Chief and Councillor of the Cree Nation of Mistissini.

|

Richard Saunders Chairman

Richard Saunders holds degrees

in Political Science and Public Administration from Carleton University. He has worked for the Assembly of First Nations, the Indian Association of Alberta, and the Ontario, Alberta and federal governments. He also served as Director of Negotiations with the Government of Nova Scotia which in 2002 signed an Umbrella Agreement with the Mi’kmaq Chiefs and the federal government. Richard was a member of the Cree-Naskapi Commission for three terms from 1986 to 1992. He has been Chairman since 1997. |

Robert Kanatewat Commissioner

Robert Kanatewat, Eeyou from Chisasibi, was instrumental in promoting the awareness of Eeyou rights as an executive member of the Indians of Quebec Association in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He was the principal plaintiff in the Kanatewat v. James Bay Development Corporation when the Cree Nation decided to oppose the initial hydroelectric development in Eeyou Istchee. He was a chief executive involved in the negotiations leading to the execution of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. For many years, he has served Eeyou of Istchee as the Executive Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees (of Quebec), Chief of the Cree Nation of Chisasibi and in various business enterprises. With the exception of one term, Robert Kanatewat has been a member of the Cree-Naskapi Commission since 1986.

|

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

CHAPTER TWO

Mandate of the Cree-Naskapi Commission . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

CHAPTER THREE

Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

CHAPTER FOUR

Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

CHAPTER FIVE

Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

CHAPTER SIX

Response of the Department of Indian Affairs and

Northern Development to the Recommendations in the

2004 Report of the Cree-Naskapi Commission . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

CHAPTER SEVEN

Recommendations of the Cree-Naskapi Commission . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .49

CHAPTER EIGHT

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .53

The Cree-Naskapi Commission has been in operation for twenty years. Although the Cree-Naskapi (of

Quebec) Act, which created the Commission, was passed in 1984, the first commissioners were not

appointed until February of 1986. Since that time the Commission has submitted nine biennial reports

on the implementation of the Act. This current report is the tenth. In addition, the Commission has

investigated many individual complaints, prepared several major discussion papers, appeared before

Parliamentary Committees and has made innumerable presentations on various aspects of the Act. To

put the period covered into some perspective, there have during the same period been ten Ministers of

Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The list includes: Crombie, McKnight, Siddon, Cadieux,

Irwin, Stewart, Nault, Mitchell, Scott and Prentice.

Looking back over that period one cannot help but notice four things:

| 1. | Very significant social, economic and governance changes have taken placed in the Cree and Naskapi communities. These have been mostly changes for the better. Unfortunately some stubborn problems remain unresolved and a few new ones have emerged. | |

| 2. | In spite of some positive and important breakthroughs, the relationships between the Cree and Naskapi governments and the federal and provincial government continue to experience problems which demand best efforts if issues are to be addressed effectively and without confrontation and litigation. | |

| 3. | The vision of the “Treaty Makers” remains. Indeed the “Treaty Makers” themselves have played key leadership roles in translating that vision into reality. Now however, as a new generation of leaders emerges, largely without having experienced the struggles which resulted in the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the Northeastern Quebec Agreement, there is a need for these generations to find time to come together and renew the vision in light of their common historical experience and present day circumstances. |

| 4. | The lessons learned during the course of recent Cree and Naskapi history are a major, but largely untapped, resource for other First Nations across Canada who are struggling to develop and implement their own vision of governance and their own approach to addressing the challenges which they face. Ways must be found to share the Cree and Naskapi experience without unduly draining scarce resources. |

It is perhaps worthwhile, before considering the specific issues addressed in the current report, to reflect briefly upon these four observations.

1986–2006: Years of Change

If one looks back to 1986 and before, and compares the life of the Cree and Naskapi communities then with the life of those same communities today, the changes are obvious and dramatic.

Clearly the overall standard of living has improved. Health in general has improved with, for example, longer life expectancy and a decline in infant mortality. On the other hand diabetes has come to be a major problem. Suicide and attempted suicide, especially among young people, has become a tragic concern in some communities. Levels of educational attainment have risen dramatically. Many successful new economic enterprises are in operation. So, in spite of some serious challenges, the past twenty years have seen a very significant improvement in the standard of living.

While living standards are important, there are other social indicators of equal, perhaps greater, importance. For example the Cree and Naskapi languages are strong and vibrant with most young people speaking their language fluently while also being fully conversant in English and/or French. This is unfortunately not the case in many other communities across the country. Also, unlike the experience in many other First Nations, there is no significant out-migration of population in the communities. In fact, there has been a comparatively large growth of population in recent years. This growth shows no signs of slackening. The high rate of formation of new families does put pressures on housing supply, education facilities and many other programs, but it also bodes well for the long term strength and viability of the Cree and Naskapi Nations. In the area of governance, Cree leaders are pursuing new initiatives to empower Cree Nation Government in ways that are consistent with Cree values and traditions but which also meet the challenges of governance in Eeyou Istchee in the 21st century. The Naskapi Nation is turning its attention to its own jurisdictional autonomy as its Inuit neighbours begin a new process of regional governance.

The Relationship with the Federal and Provincial Governments

The relationship between the Cree and Naskapi governments on the one hand and the governments of Canada and Quebec on the other, while showing some signs of solid improvement in recent years, continues to be an area of concern and of occasional dysfunctionality. In the 1998 Report of the Cree-Naskapi Commission we reported on a number of generic problems which bedevil governments especially in their relationships with First Nations. Identified as concerns at the time were the issues of limited collective awareness, limited corporate memory, and ministerial impotence. Associated with the matter of ministerial impotence was the need for bureaucratic accountability mechanisms in the area of policy management that are as strong as those in place in the area of financial management. Finally the Commission has on many occasions stressed the need for tools to ensure that Agreements and Treaties

4 Message from the Chairman

are implemented in a timely and comprehensive manner and that disputes concerning their provisions are resolved without a recourse to confrontation and litigation.

The remarkably short time in office of Ministers as noted above, highlights one of the reasons why they have had such difficulty in bring about positive change and why in fact their specific decisions usually have less than optimal impact on changing the policy direction of the department. With a few exceptions, the trend has been that Ministers are evolving into “Mini Governors General,” in the sense that they act as figureheads for a large and complex bureaucracy in which most of the real decisions are made by others. Despite their limited role in the actual decision making, it is the Ministers who are accountable in the House of Commons as well as with First Nations, the media and the public when those decisions turn out to be wrong.

The fact that real decisions are frequently made in practice by unelected and all too frequently less than truly accountable bureaucrats is a growing challenge for our democracy. This is hardly surprising given that, in the two years or so that Ministers are in office, they cannot hope to understand the historical and legal context in which Indian Affairs policy is made. The basic facts of the numerous treaties and land claims Agreements, the rapid evolution of Aboriginal law, the cultures and traditions of the more than six hundred First Nations for whom they are responsible are all matters about which even a rudimentary knowledge would require their full attention during their average two years in office. It is rare indeed for a Minister to be appointed who already has any significant knowledge of these matters. It is only with broad substantive knowledge and understanding that a Minister can begin to comprehend the full significance of the many policy and program decisions which he or she is asked to approve. It is in this environment that officials become the de facto decision makers.

Regrettably it is commonplace to hear senior officials making comments such as “the Minister hasn’t got a clue” or, “It’s hard to keep him on message” or that “he’s a loose cannon,” etc. This perceived problem is being made worse by having communications staff in each department who report to central communications officials in order to “ensure consistency in messaging” throughout the government. Ministers rarely say a word that hasn’t been scripted or at least pre-approved by unelected “communications specialists.” Typically these so-called specialists see themselves as keeping the Minister from “getting into trouble.” In fact they emasculate speeches, press releases etc. to the point that they frequently contain little of substance and at a minimum are crafted to include enough ambiguity to allow for future denial of any commitments which may have become inconvenient. Far from “keeping the Minister out of trouble,” this sort of calculated meaninglessness frequently makes Ministers appear uninformed, indecisive or simply liars.

Senior officials typically will agree on every word in a ministerial decision before the Minister ever sees it. All too often reasons will be found to justify past mistakes and to defend the status quo. In any case the final document placed before the Minister will most often reflect the thinking of only the senior officials, with options crafted so that only their recommended option is likely to be approved.

This approach may at times escape the notice of the public and the media because it has become almost the norm in the context of a political discourse which is too often geared to the avoidance of public debate on difficult choices. The “communications specialist” will strive for policy output that is as ambiguous as possible and which requires the minimum in terms of advocating, explaining or defending it in public. The current cliché stresses the desirability of “staying below the radar.”

First Nations are confronted by these twin challenges of limited ministerial control of policy and communications-based policy outputs in the context of decades of treaties broken, promises not kept and Agreements repudiated in whole or in part. They have come to accept that the battle against these barriers to change as a normal part of their task. The larger challenge for Canadians is to find ways of keeping a large and complex government democratic in more than merely symbolic ways.

The Vision of the Treaty Makers

The leaders who fought the unilateral decision of Premier Bourassa in 1971 to undertake the massive James Bay Hydroelectric Development Project without any consideration of the rights of the people whose land it had been since time immemorial, the leaders who launched the court action to block that development, the leaders who negotiated the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the Northeastern Quebec Agreement and subsequently the terms of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act were visionaries. They saw Cree and Naskapi Nations that would be strong, viable nations in control of their own destinies whose values and traditions would be practiced as effectively in the context of the twenty first century as they had been for millennia before. They negotiated Agreements under which Canada and Quebec agreed to support their rights and interests as partners, Although some of the former leaders are gone and a new generation of leaders gradually takes their places, the Cree and Naskapi leadership continues the fight to implement the letter and the spirit of the Agreements as well as the full intent of the Act. New arrangements are made as needed to address today’s realities. The 2002 Agreement

6 Message from the Chairman

Concerning a New Relationship Between le Gouvernement du Quebec and the Crees of Eeyou Istchee is an example of such a new arrangement. The current negotiations with the federal government led by Bill Namagoose and Raymond Chrétien are another. The Naskapi are now engaged in examining their own jurisdictional needs in view of the development of regional government by the Inuit of Northern Quebec.

The Treaty Makers had strong visions of what it meant to be the Cree Nation or the Naskapi Nation in the context of the pressures created by Quebec’s unilateral decisions of the time. Today three and one half decades later, a new generation is challenged to lead in the evolution of the Treaty Makers’ vision to make it a blueprint for action in the twenty first century. The old concept of “Bands”in the Indian Act sense is gone. The “Band” as envisioned in the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act is in need of some fundamental change. The communities have raised many specific suggestions for amendments to the Act which we have recommended in previous reports. What is needed now is a process of looking at what the vision of the Cree Nation and the vision of the Naskapi Nation mean today and into the future. What it means in terms of governance structures and processes, what it means in terms of language and cultural priorities, what it means in terms of economic and social priorities. Determining what this vision will be or even that a visioning process is needed is not for outsiders to decide. It is the Cree people and the Naskapi peoples to make those decisions. It is for others to accept and support the exercise of these basic rights of self-determination.

Sharing the Lessons Learned

Much of what has taken place in the last thirty-five years of Cree and Naskapi history can be of enormous value as scores of First Nations across Canada work to achieve fair and just settlements of their land claims and their efforts to restore governance structures and processes consistent with their own values and needs. Ways need to be found to share the Cree and Naskapi experience where and when it can be helpful to other First Nations. Many of the present and past leaders have shared their insights and would be happy to do so in future. The self-government and land claims support which the Department provides could increase its effectiveness by enabling the Cree and Naskapi (as well as a number of other nations) to share their experience in workshops, presentations and short term consultancies with nations currently engaged in land and/or governance negotiations.

The Cree-Naskapi Commission has now been in existence since December 1, 1984 when Part XII (Cree-Naskapi Commission) of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act came into force by proclamation of the Government of Canada. However, the first Commissioners were not appointed until February, 1986. Consequently, the year 2006 represents the 20th anniversary of the operations of the Cree-Naskapi Commission.

The Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act is the “special legislation” contemplated by section 9 of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) and section 7 of the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (NEQA). This special legislation was enacted by Parliament and assented to on June 14, 1984.

Section 9 (Local Government over Category 1A Lands) of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement provides that “there shall be recommended to Parliament special legislation concerning local government for the James Bay Crees on Category 1A lands allocated to them.” 1

Section 7 (Local Government over Category 1A-N Lands) of the Northeastern Quebec Agreement provides for similar undertakings respecting local government for the Naskapis of Quebec on Category 1A-N lands allocated to them.

The Cree-Naskapi Commission established by section 158 of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act has a duty to “prepare biennial reports on the implementation of this Act” 2 to the Minister who “shall cause the report to be laid before each House of Parliament.” 3

The present report constitutes the tenth biennial report to the Minister pursuant to sub-section 165 (1) and in accordance with sub-section 171 (1) of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act.

8 Introduction

The Commission conducts Special Implementation Hearings in order to prepare for its present report. These hearings, conducted in Montreal on February 13–16, 2006, provide an opportunity for the representatives of the Cree and Naskapi Nations and the Government of Canada to express their concerns and to discuss their issues. The findings and tone of the report are based on the Commission’s understanding and analysis on the issues and concerns raised in these hearings.

The Commission reports also on the implementation of the JBNQA and the NEQA as particular sections of these Agreements contemplate the powers and duties of the local governments of the Cree and Naskapi First Nations. The Commission reports on the implementation of these Agreements in virtue of paragraph 21 (j) of the Act which stipulates that the objects of a band are “to exercise the powers and carry out the duties conferred or imposed on the band or its predecessor Indian Act band by any Act of Parliament or regulations made thereunder, and by the Agreements.” 4

With respect to its mandate, the Commission has commented further in Chapter Two of the present report.

Over the past years, the Commission has reported on specific issues and concerns of the Cree and Naskapi Nations. Consistent themes have evolved from these issues and concerns. These themes include important needs such as:

| a) | adequate resources for housing; | |

| b) | a more effective process for the adjustment of Operations and Maintenance Funding; | |

| c) | review of and amendments to the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act; | |

| d) | effective improvements and mechanisms for the proper implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, its related Agreements and the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act; |

| e) | resources for community and economic development; | |

| f) | improvements for policing services and the administration of justice; | |

| g) | resolution for the allocation of Block D to the Cree Nation of Chisasibi; | |

| h) | responsible and effective exercise of the federal fiduciary duty to act in the best interests of the Cree and Naskapi Nations; |

|

| i) | development and implementation of an effective mechanism for the resolution of disputes; and | |

| j) | recognition for the existence, importance and continuity of Eeyou traditional law and customs. |

In Chapter Four (Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee), Chapter Five

(Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach) and Chapter Seven (Recommendations of the Cree-Naskapi

Commission) of its present report, the Commission repeats some of these themes.

Since its response to the 2002 Report of the Commission, the Department of Indian Affairs and

Northern Development has provided a comprehensive response to the recommendations of the

Commission. The responses of the Department represent an entirely different approach in its dealings

with the Commission. (Before its comprehensive response to the 2002 Report, the Department failed to

deal substantively with the recommendations of the Commission.) It appears that the Department

wants to improve its relations with the Commission as well with the Cree and Naskapi communities.

Consequently, the Commission reports and comments on these responses of the Department in its

biennial reports. Chapter six of the present report outlines and comments on the response of the

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development to the 2004 Report of the Commission.

In this manner, the Cree and Naskapi Nations are aware of the Department’s responses to their

particular issues and concerns. The Commission hopes that the communities concerned will follow-up

on these matters.

In addition, the Commission presents certain important perspectives on Cree and Naskapi governance

in its biennial reports.

Chapter Three (Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance) of the present report discusses the existence and

continuity of Eeyou law, customs and traditions and the need for formal recognition by the Government

of Canada for these traditional laws.

In its conclusions (Chapter Eight of the present report), the Commission concludes that the

Government of Canada has a legal, as well as a moral and political, duty to act in the best interests of

Aboriginal peoples.

End Notes

| 1 | James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement – 1991 Edition, les Publications du Québec, Section 9 (Local Government over Category IA Lands), para. 9.0.1, p. 172. |

|

| 2 | Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, S.C. 1984. C. 46, section 165 (1) (a). | |

| 3 | Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, S.C. 1984. C. 46, section 171 (1). | |

| 4 | Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, S.C. 1984. C. 46, section 21 (j). |

10 Introduction

The duties of the Commission are spelled out in section 165 of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act which says:

| “165. (1) The Commission shall | ||

| (a) | prepare biennial reports on the implementation of this Act, in accordance with subsection 171 (1); and |

|

| (b) | except as provided for by subsections (2) and (3), investigate any representation submitted to it relating to the implementation of this Act, including representations relating to the exercise or non-exercise of a power under this Act and the performance or non-performance of a duty under this Act. 1 |

|

Since Commissioners were first appointed in 1986, the Cree and Naskapi communities have raised issues, at almost every hearing, that arise from either the implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) or the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (NEQA). This is of course in addition to the many matters that flow from the provisions of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act. That the Agreements and the Act should both be sources (often jointly) of issues brought to the attention of the Commission is hardly surprising given that the Agreements committed Canada to introduce the Act into Parliament and that the Act itself explicitly states,

| “21. The objects of a band are … | ||

| (j) | to exercise the powers and carry out the duties conferred or imposed on the band … by the Agreements.” 2 |

|

Despite the Commission’s responsibilities in relation to “the exercise or non-exercise of powers” and “the performance or non-performance of a duty” under the Act as well as the bands’ powers and duties as described in section 21. (j) above, the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development has, from 1986 to the present time taken the position that the mandate of the Commission does not extend to consideration of matters arising under the Agreements. This view has been applied in practice repeatedly by the Department particularly when it has refused to respond to Commission recommendations which referenced the Agreements on the grounds that they were “beyond the explicit legislated mandate of the Commission”.

Most recently however the Department has begun to address such recommendations while still denying that the Commission has jurisdiction. The most recent statement of the Department’s view came during the 2006 Special Implementation Hearings in Montreal. On February 13, 2006, Michel Blondin, Director of the James Bay Implementation Office, said:

- “ … as you know, INAC’s view has been that the Commission does not have jurisdiction

to investigate and make recommendations on the implementation of the James Bay and

Northern Quebec Agreement and the Northeastern Quebec Agreement, and that is still

the federal position.” 3

That may indeed be the federal position when speaking in Canada however the government takes the opposite position when extolling its accomplishments at the United Nations. For example, when explaining how well Canada implements its agreements with Aboriginal peoples and how it resolves disputes arising out of those agreements the federal government frequently cites the role of the Cree-Naskapi Commission. During a presentation to the United Nations Seminar on Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements Between States and Indigenous Peoples, held December 15 to 17, 2003, Canada’s representative said:

- “The first of the modern treaties, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA),

provides for a monitoring mechanism, namely the Cree-Naskapi Commission.” 4

When informed of this obvious contradiction at the February 13, 2006 hearing, Mr. Blondin replied:

- “I have someone to kill, that’s all. That was just a joke – it’s a joke.” 5

Interestingly the presentation to the United Nations quickly disappeared from the Department’s Web site where it had been available to the public for the previous two years. The Commissioners had not mentioned to Mr. Blondin that a much more explicit statement of the government’s position was also on the Department’s official website and remains there as this report is being written. This statement reads as follows:

- “Part XII of the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act provided for the creation of the Cree-Naskapi

Commission to privately investigate complaints arising from the James Bay and Northern

Quebec Agreement, the Northeastern Quebec Agreement or the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec)

Act implementation or lack thereof.” 6

12 The Mandate of the Cree-Naskapi Commission

relation to the Agreements when it is at the same time telling the United Nations as well as the

Canadian public that the Commission does indeed have such jurisdiction. When the government then

cites this as an example of how well Canada implements agreements and resolves disputes arising out

of their provisions, its position becomes simply comical.

In any event, the Commission will continue to address issues raised by individuals, communities and

governments whenever they relate to the Act or to relevant provisions of the Agreements.

End Notes

| 1 | Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, section 165. (1). | |

| 2 | Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act, section 21. (j). | |

| 3 | Cree-Naskapi Commission, Special Implementation Hearings, Montreal, February 13, 2006 (official transcript p. 1, lines 34–39). | |

| 4 | Canada, “Government of Canada Perspective on Treaties, Agreements and Constructive Arrangements Between the States and Indigenous Peoples,” United Nations Seminar, December 15–17, 2003. | |

| 5 | Cree-Naskapi Commission, Special Implementation Hearings, Montreal, February 13, 2006 (official transcripts p. 15, lines 17–18). | |

| 6 | Indian and Northern Affairs Canada website, page “Hybrid Processes” para. 4. |

Introduction

The Eeyouch (Cree) exist as a people and as a nation with their aboriginal and treaty rights, basic human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee (Cree Nation of the Cree Territory) consider themselves as a self-governing people who were, before contact with the European peoples, fully independent and an organized society occupying and governing their land as their forefathers have done for centuries. Although this self-governing status was greatly diminished by the encroachments of outside governing regimes, it managed to survive in an attenuated form.

The sovereign claims and colonial regimes of the European powers were established in virtual disregard of the fact that Eeyou Istchee (Cree traditional and historical territory) was already occupied and used by self-governing Eeyou people.

For Eeyouch, there is no more basic principle in Eeyou history and relations than a people’s right to govern themselves and their territories in accordance with their traditional laws, customs, values and aspirations. Therefore, as far as Eeyouch are concerned, Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee have an inherent right of Eeyou governance.

This right is inherent in the sense that it finds its ultimate origins in the collective lives, traditions and Eeyou law and history rather than the Crown or Parliament. In particular, the inherent right to Eeyou self-government flows from the original and present occupation of Eeyou Istchee by Eeyouch. In this

14 Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance

regard, Eeyou Tapay-tah-jeh-souwin (Eeyou governance) isn’t something that’s going to happen in the future. It’s something that has happened, is happening and will continue to happen in accordance with Eeyou law, rights and aspirations. After all, Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee have always been a self-governing people.

The right of Eeyou governance inheres in the Eeyou nation. Consequently, it is through the nation that Eeyouch express their personal and collective autonomy.

In 1982, Aboriginal and treaty rights were embodied in the written constitution of Canada for the first time in Canadian history. In particular, section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, states that the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognised and affirmed.”

In its Report of 1996, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples concluded “that the inherent right of self-government is one of the existing Aboriginal and Treaty rights” recognised and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

Aboriginal rights evolve from prior occupation of lands by Aboriginal Peoples and prior social organization and distinct cultures of Aboriginal Peoples. In Van der Peet 1 the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada stated:

- In my view, the doctrine of aboriginal rights exists, and is recognised and affirmed by s. 35(1),

because of one simple fact: when Europeans arrived in North America, aboriginal peoples were

already here, living in communities on the land, and participating in distinctive cultures, as they

had done for centuries. It is this fact, and this fact above all others, which separates aboriginal

peoples from all other minority groups in Canadian society and which mandates their special

legal, and now constitutional, status. 2

- Aboriginal rights arise from the prior occupation of land, but they also arise from the prior social

organization and distinctive cultures of aboriginal peoples on that land. In considering whether a

claim to an aboriginal right has been made out, courts must look at both the relationship of an

aboriginal claimant to the land and at the traditions, customs and traditions arising from the

claimant’s distinctive culture and society. Courts must not focus so entirely on the relationship

of aboriginal peoples with the land that they lose sight of the other factors relevant to the

identification and definition of aboriginal rights. 3

The Supreme Court affirmed in Adams 4 that these practices, customs and traditions did not require the formal recognition of Europeans in order to be protected:

- The fact that a particular practice, custom or tradition continued following the arrival of Europeans,

but in the absence of the formal gloss of legal recognition from the European colonizers should

not undermine the protection accorded to aboriginal peoples. Section 35 (1) would fail to achieve

its noble purpose of preserving the integral and defining features of distinctive aboriginal societies

if it only protected those defining features which were fortunate enough to have received the legal

approval of British and French colonizers. 5

Madam Justice McLachlin wrote on the recognition by the common law of the ancestral laws and customs of Aboriginal Peoples in her Reasons in Van der Peet. 6

- The history of the interface of Europeans and the common law with aboriginal peoples is a long one.

As might be expected of such a long history, the principles by which the interface has been governed

have not always been consistently applied. Yet running through this history, from its earliest beginnings

to the present time is a golden thread – the recognition by the common law of the ancestral laws and

customs the aboriginal peoples who occupied the land prior to European settlement. 7

Furthermore, Madam Justice L’Heureux-Dubé spoke of the doctrine of continuity in the context of an approach to interpreting the nature and extent of aboriginal rights. Justice L’Heureux-Dubé wrote: 8

- … Instead of considering it as the turning point in aboriginal culture, British sovereignty would be

regarded as having recognized and affirmed practices, traditions and customs which are sufficiently

significant and fundamental to the culture and social organization of aboriginal people. This idea

relates to the “doctrine of continuity,” founded in British imperial constitutional law, to the effect that

when new territory is acquired the lex loci of organized societies, here the aboriginal societies,

continues at common law. 9

It could not have been only specific traditional laws that were continued but rather the jurisdiction of aboriginal governments to formulate, enact and enforce laws. 10

It is clear that the Supreme Court of Canada affirms and acknowledges the existence and continuity of aboriginal traditional law and customs.

Eeyou governance has evolved from long-standing practices based on Eeyou law, traditions and customs. However, Eeyou governance has also evolved from the implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act.

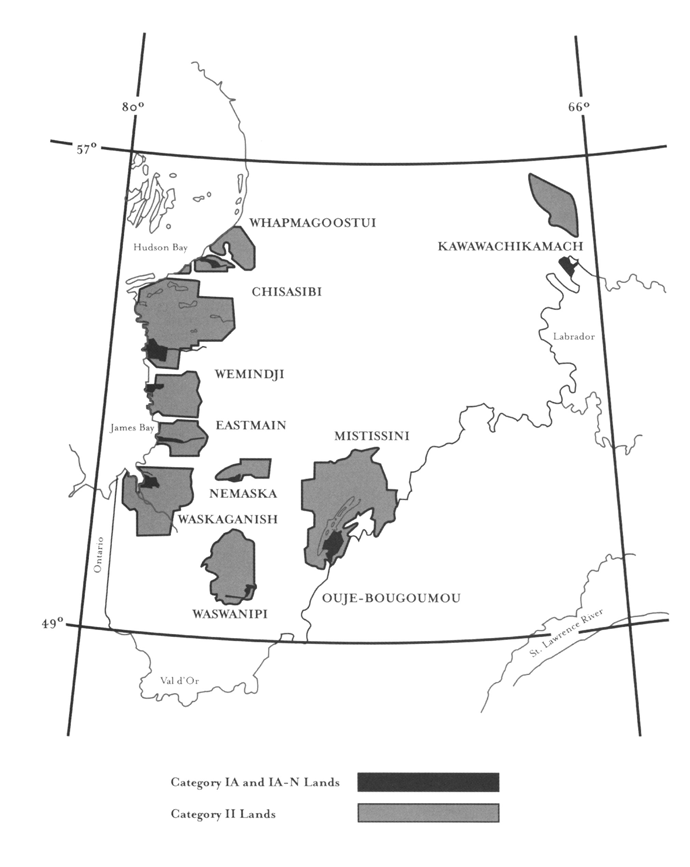

Pursuant to the terms and provisions of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA), Eeyou Istchee was carved out into three (3) categories of land. Lands classified as Category 1A, under federal

16 Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance

jurisdiction, and Category 1B, under provincial jurisdiction, were set aside and allocated to the Cree for their exclusive use and benefit and under the administration and control of Cree local governments.

Pursuant to federal obligations to Eeyouch (Cree and Naskapi Nations) under the JBNQA and NEQA, special federal legislation – the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act – enacted by Parliament and assented to on June 14, 1984 – provides for an orderly and efficient system of Cree and Naskapi local government and for the administration, management and control of local community lands by the Cree and Naskapi First Nations. The Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act replaces the Indian Act for the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee and the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach. During the course of negotiations leading to the signing of the JBNQA, Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee rejected the restricted, supervised and imposed local government regime of the Indian Act. Consequently, except for the purpose of determining which of the Cree beneficiaries and Naskapi beneficiaries are “Indians” within the meaning of the Indian Act, the Indian Act does not apply to the Cree and Naskapi First Nations nor does it apply on or in respect of their community lands.

Moreover, the Indian Act fails to take into account tradition law, customs and practices for governance.

Notwithstanding the legal regime of local government under the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act and other powers and responsibilities of Eeyou for Governance under the JBNQA, its related Agreements and subsequent legislation, Eeyouch continue to incorporate Eeyou law, traditions and customs in the exercise and practice of local government and Eeyou nation governance. (With the exception of provisions relating to Part XIII – Successions, the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act is silent on the existence and continuity of Eeyou law, customs and traditions.)

The present chapter explores the origin and nature of Eeyou law, traditions and customs.

Eeyou Weesou-wehwun, Eeyou Eedou-wun and Eeyou Kas-jeh-hou-wun

(Eeyou Law, Eeyou Customs and Traditions, and Eeyou Rights)

The Eeyouch have exercised and will continue to exercise their right of self-determination which is referred to as “Weesou-way-tah-moo-wun” in the language of the Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee. The words “Eeyou weesou-way-tah-moo-wun” are best described as “determination by Eenou” or Eeyou self-determination which is the power of choice in action.

The exercise and practice of Eeyou Tapay-tah-jeh-souwin (Eeyou governance) has evolved from the exercise of Eeyou weesou-way-tah-moo-wun (Eeyou self-determination).

The Cree people, as they are called by contemporary society, have the collective and individual right to maintain and develop their distinct identity and characteristics. In particular, the Cree people have the right of self-identification and they identify themselves, as they have done for millennia, as Eeyou/Eeyouch and Eenouch/Eenou. Furthermore, Eeyouch have the individual and collective right to a nationality and to be recognised as a distinct nation. Eeyouch have a right to belong to an Eeyou community and an Eeyou Nation within their traditional and historical homeland, which Eeyouch call Eeyou Istchee. Consequently, the so-called James Bay Crees are Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee. (The word “Cree” has its origins from the French and English peoples).

Eeyou Istchee is the totality of community and traditional and historical hunting territories of the Eeyouch. Eeyou Istchee is the land that Eeyouch have used and occupied for millennia. Therefore, Eeyou Istchee is essential and central for the “meeyou pimaat-tahseewin” or holistic well-being of Eeyouch. The centrality of Eeyou Istchee forms the foundation of Eeyou governance, Eeyou culture, identity, history, spirituality and the traditional way of life. This unique and special relationship between Eeyouch and Eeyou Istchee – is part of the nature of ‘being Eeyou/Eenou.’

The Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee refer to the Eeyou right of self-government or any Eeyou right as “Eeyou Kas-jeh-hou-wun” which means Eeyou power or ability given by human authority or by a divine source. This inherent right (of self-government) is exercised by and through the Eeyouch which is the historical and traditional authority of governance. It is through the nation or people that the Eeyouch express their personal and collective autonomy. This practice or exercise of governance through the Eeyou nation or people is described as “Eeyou Tapay-tah-jeh-souwin” by the Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee. Furthermore, the Eeyouch have, by Eeyou law, established their Eeyou land tenure system of Eeyou Indoh-hoh Istchee (Eeyou hunting territories) with the governing authority of the Indoh-hoh Ouje-Maaoo (Hunting Governor or Tallyman). This Eeyou land tenure system was determined and established by “Eeyou Weesou-wehwun” (Eeyou law-making).

“Eeyou Kas-jeh-hou-wun” in the Eeyou language means “Eeyou capacity or power.” “Eeyou Kas-jehhou-wun” are the words used by the Eeyou/Eenou leadership to express the fundamental principle of Eenou/Eeyou rights.

“Eeyou Eedou-wun” in the Eeyou language means “Eeyou/Eenou way (of doing things).” “Eeyou Eedou-wun” are the words used by the Eeyouch to express the concept of customs and traditional practices.

18 Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance

“Eeyou Weesou-wehwun” in the Eeyou language means “Eeyou law” (as a direct result of Eeyou decision-making). “Eeyou Weesou-wehwun” are the words used by the Eeyou/Eenou leadership to express the concept of Eeyou law inherent in Eenou/Eeyou society. Consequently and subject to Canadian law and jurisprudence affecting Aboriginal “customary/traditional” law, Eeyou Weesou-wehwun is distinct from Aboriginal law (contemporary law affecting Aboriginal peoples). One must note the similarity of the Eeyou words “Eeyou Weesou-wehwun” (Eeyou law) and “Eeyou Weesou-way-tah-moo-wun” (Eeyou self-determination).

In the exercise of Eeyou Tapay-tah-jeh-sou (Eeyou government) Kas-jeh-hou-wun (right) or the inherent right of self-government, the Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee have determined and will continue to determine Eeyou Weesou-wehwun or Eenou law. The Eeyouch have also determined and will continue to determine Eeyou Eedou-wun or customs and traditions. In this manner, the Eeyouch will continue to shape Eeyou culture.

Eeyou law is the body of law inherent in Eeyou. It is a body of law passed down from generation to generation. Eeyou law manifests the common value of Eeyou society. For the Eeyouch, Eeyou law, custom and tradition do not consist of static principles, practices and institutions from the distant past. They constitute an evolving body of ways of life that adapts to changing situations and readily integrates new attitudes and practices. Consequently Eeyou law is not a static body of law; but is an evolving body of principles and norms of life in Eeyou society.

The Eeyouch, like other contemporary people, are constantly reworking their institutions to cope with new circumstances and demands. In doing so, they freely borrow and adapt cultural traits that they find useful and appealing. In this regard, Eeyou law can be regarded as a continuing process of attempting to resolve the problems of a changing society, than a set of rules .It is not the heedless reproduction of outmoded practices that makes an effective Eeyou law and a vigorous tradition, but a strong connection with the living past especially a strong and living connection with the land – Eeyou Istchee.

It is often said that ‘custom makes law.’ For the Eeyouch, Eeyou law may flow from Eeyou customs and traditional practices. However, traditions appeal to values and actions that sustain customs. In fact, Eeyou values form the building blocks for the ethical principles which form the basis for Eeyou law and tradition. Consequently, Eeyou law and tradition flow from Eeyou values and principles.

In addition, Eeyou culture may be defined simply as the way of life adopted by the Eeyouch. In fact, Eeyouch describe Eeyou culture as “Eeyou pimaat-seewun” (Eenou way of life). For the Eeyouch, culture is determined by Eeyou Eedou-wun – the Eeyou way of doing things – and encompasses the complex whole of beliefs, values, principles, practices, institutions, attitudes, morals, customs, traditions and knowledge. These elements influence the determination of Eeyou law as Eeyouch know what values and principles are Eeyou law.

In summary and in consideration of the Eeyou legal system, one must consider the following important aspects of Eeyou society and contemporary law:

| a) | Eeyou right of self-determination or Eeyou weesou-way-tah-moo-wun; | |

| b) | Eeyou Tapay-tah-jeh-sou (Eeyou government) Kas-jeh-hou-wun or the inherent right of self-government; |

| c) | Sovereignty of Eeyou; | |

| d) | Eeyou Weesou-wehwun or Eeyou law as determined and established through the Eeyou decision-making process; |

|

| e) | Rule of Eeyou law; | |

| f) | Eeyou Eedou-wun or Eeyou way of doing things (i.e. customs and practices); | |

| g) | Eeyou Pimaat-seewun (Eeyou way of life or culture); | |

| h) | Centrality and fundamentality of Eeyou Istchee; | |

| i) | Eeyou spirituality; | |

| j) | Eeyou land tenure system or the Indoh-hoh Istchee System; | |

| k) | Application of traditional institutions; | |

| l) | Autonomy, responsibilities and powers of the Indoh-hoh Ouje-Maaoo (Eeyou Hunting Governors or Tallymen); | |

| m) | Powers, duties and responsibilities of the Eeyou Ouje-Maaooch (Eenou/Eeyou leaders and authorities); | |

| n) | Powers, duties and responsibilities of the Eeyouch Tapaytahchehsouch (Eeyou local and Nation (regional) governments); | |

| o) | Individual autonomy and responsibility; | |

| p) | Respect for authority; | |

| q) | Roles of women and elders; | |

| r) | Roles and responsibilities of the family and clan; | |

| s) | Leaders and the process of leadership; | |

| t) | James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and other related Agreements/Treaties including enabling federal and provincial legislation; | |

| u) | Aboriginal law; | |

| v) | Eeyou process and consensus in decision-making; and | |

| w) | Application of other Eeyou values, rights and principles. |

In summary, Eeyou law is:

| a) | is conventional, customary and unwritten; | |

| b) | embodied in oral traditions and community observances; | |

| c) | passed down from one generation to another; | |

| d) | an evolving body of principles and norms of Eeyou life; and | |

| e) | focused on core Eeyou values and principles and subsequently manifests the common value of Eeyou society. |

20 Eeyou Law and Eeyou Governance

Conclusion

Eeyou governance has evolved dramatically over the past three decades mainly in response to the fundamental changes in the political, social and economic landscape of Eeyou Istchee. This evolution of Eeyou governance is customary and natural as political power is universal and inherent in human nature. After all, Eeyou self-determination is the power of choice in action. In many instances, Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee have adopted a “just do it” approach.

Consequently, the meaning and practice of Eeyou governance has evolved and has been redefined by Eeyouch on the basis of Eeyou law, rights, freedoms, value, culture, customs, traditions, aboriginal law and the intent and spirit of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and its related Agreements such as the Agreement Concerning a New Relationship Between le Gouvernement du Québec and the Crees of Quebec and the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act.

Eeyou governance has definitely evolved dramatically over the last quarter of the past century beyond the Indian Act, Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act and the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.

The reconciliation of pre-existing and inherent Eeyou rights and Eeyou law with the sovereignty of the Crown has been, and continues to be, a major political, legal/constitutional and socio-economic challenge.

In order for Eeyou and Canada to work together, Canada must explicitly recognize the inherent right of Eeyou governance and the existence and continuity of Eeyou laws and traditions within its constitutional and fundamental laws. The courts have already recognised the existence and continuity of the laws, traditions and customs of Aboriginal Peoples including aboriginal decision-making, regulation, and indeed Aboriginal governance.

For Eeyouch of Eeyou Istchee, mutual recognition of coexisting and self –governing peoples and nations is basic and fundamental in the continuing Eeyou relationships and partnerships with Canada and Quebec.

End Notes

| 1 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507. | |

| 2 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507. | |

| 3 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507 at para. 74; R. V. Adams, [1996] 3 S.C.R. 101 at para. 29. | |

| 4 | R. v. Adams, [1996] 3 S.C.R. 101. | |

| 5 | R. v. Adams, [1996] 3 S.C.R. 101 at para. 33. | |

| 6 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507. | |

| 7 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507 at para. 263. [Emphasis added] | |

| 8 | Peter W. Hutchins with Kalmakoff. “The Golden Thread of Continuity, the Federalism Principle and Treaty Federalism – Where’s the Gap?” Paper for presentation to the Canadian Aboriginal Law 2005: The Shifting Paradigm, at p. 13, 14. | |

| 9 | R.v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507 at para. 173. [Emphasis added in original] | |

| 10 | Peter W. Hutchins with Kalmakoff. “The Golden Thread of Continuity, the Federalism Principle and Treaty Federalism – Where’s the Gap?” Paper for presentation to the Canadian Aboriginal Law 2005: The Shifting Paradigm, at p. 14. |

In preparation for its 2006 report, the Cree-Naskapi Commission conducted its Special Implementation Hearing on February 13–16, 2006 in Montreal, Quebec. Representatives of the Eeyou (Cree and Naskapi) Nations and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development presented written and oral submissions to the Commission at this special hearing.

Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee)

On February 16, 2006, Mr. Bill Namagoose and Chief Billy Diamond, representatives of the Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee) presented a submission to the Commission on the following issues and concerns:

1. Implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA)

According to the representatives of the Grand Council of the Crees, the implementation of the JBNQA – a modern day Treaty – has been, so far, a long, difficult and acrimonious process entailing reviews, negotiations, litigation and mediation on certain provisions of the Agreement. Certain sections of the JBNQA remain to be implemented properly. As an example, the application of section 22 (Environmental and Social Protection) remains to be properly implemented by the Government of Canada which has decided to unilaterally apply the federal regime of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. The regime established by and in accordance with section 22 of the JBNQA is the

22 Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee

In 2002, the Eeyou Nation of Eeyou Istchee and the Government of Quebec negotiated and accepted the Agreement Concerning a New Relationship Between le Gouvernement du Québec and the Crees of Quebec which is also known as the Paix des Braves. In this Agreement, the Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee assume certain obligations of Quebec under the JBNQA for a period of fifty years with indexed annual funding. This particular arrangement which is an innovative way of implementing certain sections of the JBNQA has enabled the Eeyou governments and leadership to decide on the implementation of programs and services which meet their priorities and needs as determined by Eeyou authorities. In the past, priorities and programs were often debated with non-Eeyou authorities. 2

Since the execution of the JBNQA which was signed by the Eeyou, Canada and Quebec Governments in 1975, the Eeyou Nation of Eeyou Istchee has sought the proper implementation of the JBNQA with the Government of Canada. Certain Agreements such as the Operation and Maintenance Agreement and the Agreement Respecting Cree Human Resources Development have been achieved by Eeyou and Canada. However, Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee sought a new relationship with Canada – a new relationship that should have evolved if the spirit, intent and letter of the JBNQA had been properly respected and honoured by the Government of Canada.

2. New Relationship Between Eeyou (Cree) and Canada

Recently, the Eeyou and federal negotiators, through the Chrétien-Namagoose process, have made some progress in negotiating an agreement on a new relationship between Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee and the Government of Canada in a manner which sets out an acceptable way of implementing Canada’s obligations to the Crees under the JBNQA.

In August 2004, the Eeyou and Federal negotiators signed a joint statement of intent which sets out the intentions of the parties to negotiate an agreement on the following matters:

| a) | establishment of a Cree Regional Government; | |

| b) | resolution of outstanding issues and of the court proceedings to the extent possible; and | |

| c) | setting up a dispute resolution process. 3 |

In June 2005, the Eeyou and federal negotiators signed a document entitled: Outline for Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Cree Nation of Quebec. This document outlines the progress made on the following issues:

| a) | establishment of the new relationship between Canada and the Cree Nation; | |

| b) | improvement of the implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement; | |

| c) | commitment to move forward towards a Cree Nation Government with the means to function and a Cree Constitution, to be recognised by Canada, to guide its operations; |

| d) | assumption by the Cree Government of certain obligations of Canada in the JBNQA and of certain programs of the Government of Canada, for the term of the agreement; | |

| e) | greater responsibility of the Cree Nation for its own economic development and increased ability to maintain relations with other governments; and | |

| f) | resolution of court cases and disputes and the setting up of a dispute resolution process. 4 |

In December 2005, a final agreement was achieved by the negotiators of the Eeyou Nation and the Government of Canada. This Agreement was approved by the Federal Steering Committee that oversaw the negotiations for the Government of Canada and by the Board of Directors of the Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee).

However, the Government of Canada under Prime Minister Paul Martin fell and a federal election was called. Consequently, the parties decided to leave the execution of this Agreement until after the federal election. (The federal election held in January, 2006, resulted in the election of a new government under Prime Minister Stephen Harper.)

According to Mr. Bill Namagoose, the Eeyou negotiator, the “proposed agreement is the culmination of many years of efforts on the part of all of the three previous Grand Chiefs and the present administration. I firmly support this agreement and hope that the new Federal Government of Prime Minister Harper will embark on this new Canada – Cree relationship with us.” 5

The Grand Council of the Crees requests the Cree-Naskapi Commission to “monitor the process relating to the treatment of this issue in the forthcoming months until the related Agreements are signed.” 6

24 Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee

3. Cree Housing

The provision of housing has always been a priority for the Cree and Naskapi Nations. The Cree-Naskapi Commission in its past reports has reported on the housing situation for the Cree and Naskapi communities.

Chief Billy Diamond, representative of the Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee), made a presentation on the housing situation in the Eeyou communities as follows:

The Cree housing situation is the most difficult one to resolve and is presently in a crisis state.

In a 1999 survey on the Cree housing situation, the findings were as follows:

| a) | 2,423 units existed but 1,403 units or 58% more were needed; | |

| b) | 60% of the units were over-crowded by Canadian standards; | |

| c) | 1,297 units had an occupancy rate greater than 1 person per room; and | |

| d) | Crees had the worst persons per house ratio (5.2) of all other aboriginal Nations in Quebec as compared to 4.0 for other First Nation communities and 4.1 for Nunavik. 7 |

Indian Affairs has always used an average of 4.0 persons as an ideal planning measurement. The Cree study indicates that the ideal persons per house ratio for planning purposes should be 3.5 based on Cree demographics.

The number of houses that the Cree communities have constructed over the last 5 years has not kept pace with the increasing family units formation so the backlog and overcrowding of houses have increased.

The new family formations are presently running at about 120 a year. The Cree communities have constructed about 55 units a year through assistance from the CMHC. This number was increased to 78 units for 2005–2006 and 2006–2007 as a result of new one-time funding. However because of a new allocation process, the Cree share of the regular CMHC envelope will drop from 78 to 26 units for the subsequent years. Because of the inequitable result, the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee disputes this new allocation process. 8

In a letter addressed to the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and dated July 11, 2005, the then Grand Chief Ted Moses states that the new allocation process is “unacceptable in that it is contrary to our existing agreements, understandings and past practices and is in complete contravention of the spirit and scope of our new relationship discussions.”

The allocation process and its consequences remain to be resolved with the Government of Canada.

Presently, the backlog of housing units needed in the Cree communities continues to increase resulting in more overcrowding of housing units. This has negative repercussions on the social well-being of the individuals and families.

Contrary to a national trend among aboriginal communities, the Crees are not, in substantially increasing numbers, leaving their communities and territories to become part of a steadily growing off-reserve population. This is an important fact, as policy makers tend to rely on national trends to determine

housing allocation for First Nations. The new housing allocation process ignores the Cree reality of an increasing and remaining on-reserve population. Therefore, the Crees believe that they have not been receiving their equitable share of housing program funding from Indian Affairs and CMHC for the past 20 years. This inequitable allocation of housing resources from Canada remains to be resolved as it results in the existing and increasing backlog of housing units for the Cree communities. Housing resources have not been sufficient to meet the rising demands. 9

As far as the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee is concerned, community development which includes housing and infrastructure and Cree Nation building constitute one of the fundamental promises made to the Crees in the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. However the Government of Canada has taken the position that the JBNQA has not created an obligation for Canada to provide housing to the Crees other than what is available from programs of general application. 10

Furthermore, the representative of the Government of Canada has stated that the JBNQA does create an obligation for housing for the Inuit party. The Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee question the logic that results in different housing benefits for the two Native parties to the same Agreement. 11

In addition, the Cree consider the execution and proper implementation of the JBNQA as defining a new Cree-Canada relationship which encompasses the provision of community development including housing. The provision of housing through programs of general application does not in itself constitute an element of a new Cree-Canada relationship.

In addition to the provisions of the JBNQA, the Commission considers that the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee, like other First Nations of Canada, is entitled to benefit from programs of general application.

On November 3, 2005, the Cree Housing Side Table of the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee submitted to the Federal Negotiation Team a proposal entitled “The Cree Proposal to Resolve the Housing Crisis in James Bay.” The Cree consider their proposal a well-balanced and reasonable one in which the Cree are prepared to commit a substantial amount of Cree public and private funds to resolve the housing problem and create new economic opportunities.

According to the Cree, the present backlog for housing is 1,548 units as compared to the total existing housing stock of 3,001 units for a deficiency rate of 52%. The backlog is the primary cause of severe overcrowding of houses in the Cree communities. From the total present housing stock, 213 units or 7% are substandard to the extent that they should be condemned and replaced and a further 913 units or 30% require major renovations due to overcrowding. 12

The Cree Housing Proposal to the Government of Canada contains the following elements

and considerations:

| 1) | The Cree Regional Housing Authority would be established under the auspices of the Cree Regional Authority and would ultimately be governed by the Cree Nation Government. | ||

| 2) | Canada guarantee Capital Funding under existing DIAND programs for the Crees. This guarantee would provide that an ‘A Base’ funds would be guaranteed for the term of the Agreement – 20 years and that the index in the agreement would be modified. |

26 Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee

| 3) | CMHC funding will be transferred to the Cree Regional Housing Authority and increased to an amount of $10 million dollars indexed for price and population. In respect to Cree housing, the role of CMHC would be transferred to the Cree Regional Housing Authority. |

|

| 4) | The Crees will provide from their own monies funding an amount of approximately $310 million over 20 years to fund a portion of the housing and development costs. |

|

| 5) | The Government of Canada will undertake to retire all direct and indirect housing debt relating to all CMHC housing projects. |

|

| 6) | A payment in the amount of $450 million will be provided upfront to the Cree Regional Housing Authority (or a recipient of funding to be designated) to fund the capital costs of housing, renovation and infrastructure development relating to new serviced lots. |

|

| 7) | A key principle of the Cree Housing Proposal is that there will be no free housing provided; only affordable housing and that incentives for private ownership will be taken into account in all aspects of program design and delivery. 13 |

The Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee hopes that the Commission will encourage the Minister of Indian Affairs to consider and support the Cree Housing Proposal.

4. Other Issues

In addition to the implementation of the JBNQA issues and concerns, the representatives of the Grand Council of the Crees raised outstanding issues such as the implementation of the Ouje-Bougoumou Agreement, Nemaska and Waswanipi relocation, access road issues, transmission line issues and issues relating to the Washaw Sibi and MoCreebec Cree Nations.

Cree Nation of Washaw Sibi

Chief Billy Katapatuk Sr. and Mr. Kenneth Weistche, on behalf of the Cree Nation of Washaw Sibi, made a presentation to the Commission on the following issues and concerns:

Implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and the Washaw Sibi Eeyou

The representatives of the Washaw Sibi Eeyou consider their situation as a fundamental issue respecting the implementation of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. The Washaw Sibi Crees are beneficiaries of the JBNQA; but do not receive the full scope of the benefits of the Agreement. As they do not reside on Category 1 lands, they do not benefit fully from the JBNQA. They claim “that the Government of Canada has forcibly relocated our members to a reserve which never had any possibility of becoming Category 1 land. The Government of Canada failed to live up to its fiduciary obligation toward us.” 14

They consider that Canada has the moral, if not legal, obligation to take the appropriate measures to ensure that the Washaw Sibi Eeyou can enjoy the full benefits of the JBNQA.

The Washaw Sibi Eeyou claim to exist as a distinct group with their own historical and traditional hunting territories in the Harricana watershed. This claim is supported by preliminary anthropological findings and linguistic evidence.

The representatives of the Washaw Sibi Eeyou stated that they continue “to live as minority members of

the Algonquin community of Abitibiwinni. We have continued to be the last to receive the benefits of

the meager programs and services available to typical Indian Act bands. Our members have been told by

Abitibiwinni officials that since we are Cree beneficiaries we should obtain educational and health services

from the appropriate Cree institutions. Of course, such services by Cree institutions are not available to

us as we do not reside on Category 1 lands. This unresolved situation has resulted in our people having

neither full benefits of membership in the Abitibiwinni First Nation nor the full range of benefits to

which beneficiaries of the JBNQA are entitled. In this administrative vacuum we have suffered and in

some instances this has resulted in tragic consequences with our people unable to receive emergency

medical attention.” 15

The Washaw Sibi Eeyou further claim that this historical injustice “stems from the failure of the

Government of Canada to fulfill its solemn duty to protect and defend the interests of the Washaw Sibi

people when it participated in the coercion of our people to live outside of our traditional territory in a

minority position within the Abitibiwinni Reserve.” 16

In the summer of 2006, the Washaw Sibi Eeyou demonstrated their commitment and determination

to improve their situation by taking a trek of 120 kilometers back to their traditional lands where they

took up residence in a rudimentary village. They are calling on the Government of Canada for assistance

in establishing a new village for the Washaw Sibi Eeyou.

The Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee has commenced serious discussions with the Government of Canada,

through the Chrétien-Namagoose process, for an acceptable way of implementing Canada’s obligations

to the Crees under the JBNQA. In the context of these discussions, the issues and concerns of the

Washaw Sibi Eeyou have been raised. The representatives of Washaw Sibi Eeyou have participated

in this process to clarify questions raised concerning them. Washaw Sibi Eeyou have stated that a

resolution of their issue would require a financial commitment from Canada for the purpose of

constructing a new village.

The Washaw Sibi Eeyou “consider that it would be appropriate for the Commission to:

| 1. | use the office of the Cree-Naskapi Commission to continue to bring to the attention of the Government of Canada its failure to fulfill its fiduciary obligations to the Washaw Sibi Eeyou, and that this is both a moral and legal obligation; and |

|

| 2. | urge the Government of Canada, both formally and informally, to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the Chrétien Process to recognize Washaw Sibi as the tenth Cree First Nation and to immediately commit to financing the construction of a Washaw Sibi village within the framework of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.” 17 |

Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation

Deputy Chief Sophie Bosum and other representatives of the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation spoke on the following matters:

28 Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee

Operations and Maintenance Funding

The Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation remains very concerned about their Operations and Maintenance funding. Ouje-Bougoumou continues to be concerned about the amount and basis of the adjustment to the funding levels of the O&M funding.

As a result of funding from the new relationship agreement with Quebec, Ouje-Bougoumou has constructed new facilities for their community. But the Government of Canada has so far failed to acknowledge its obligations and responsibility to fund the operations and maintenance of these new capital facilities. Clearly, as far as Ouje-Bougoumou is concerned, “the Government of Canada has an obligation under the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act to make O&M funding available to the communities for its operating needs.” 18

Consequently, Canada has not maintained pace with these developments in the provision of O&M funding for new capital facilities.

Furthermore, Ouje-Bougoumou is concerned about the inadequacy of current funding levels to address the present and future community needs and services such as “increased office computerization, communications (for example, the internet), elders care, youth programming, operation and maintenance of recreation facilities, urgent cultural programming needs, local level legal work to defend Cree rights, and local structures to administer justice.” 19

The Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation once again recommends “a review of the O&M funding formula towards the end of incorporating a financial capacity to address new needs in the communities which were never contemplated in 1984 when the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act came into force.” 20

The Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement stipulates that the funding available to the other Cree communities will not decrease as a result of funding which would be available to Ouje-Bougoumou for capital projects. The DIAND maintains that it is not required to reimburse the Crees for funding received by Ouje-Bougoumou for capital projects since 1994–1995. A total amount of $1.7 million had been transferred to Ouje-Bougoumou from the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee for capital projects since 1994–1995.

Outstanding Claim of Ouje-Bougoumou

With respect to funds transferred under the Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement, the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation maintains a claim for an amount of $2,952,000 which constitutes the loss of earnings emanating from the late payment of agreed upon amounts under the Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement and indirect costs. According to the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation, this amount is owed to Ouje-Bougoumou and should be paid by the Government of Canada.

Implementation of the Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement

About fifteen (15) years have elapsed since the execution of the Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement and the Crees and Canada have not entered into a Complementary Agreement amending the JBNQA. This Complementary Agreement would incorporate the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation into the JBNQA as intended and contemplated by the Ouje-Bougoumou/Canada Agreement. This situation leaves the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation in a legal vacuum in respect to the legality of their by-laws and ability to act as a Cree band.

According to the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation, the “discussions to date can only be described as frustrating, seemingly endless and costly.” 21

However, the Ouje-Bougoumou Cree Nation remains hopeful that this issue and other matters can be resolved within the context of the current Cree-Canada discussions.

Cree Nation of Wemindji

Deputy Chief Arden Visitor spoke on the following issues and concerns:

Implementation Mechanism

Many recommendations of the Commission reflect the aspirations of the Cree communities for the proper and full exercise of the inherent right of self-government. However, these recommendations lack an implementation process or mechanism. The Cree Nation of Wemindji states that it “is paramount that each local government from the Cree and Naskapi and especially from the Grand Council of the Crees, collaborate to prioritize in the development of the Implementation Mechanism for the Cree-Naskapi Commission.” 22 The Commission should facilitate, in collaboration with the Eeyou local governments and the Grand Council of the Crees, the process for the development and implementation of the Implementation Mechanism.

30 Issues and Concerns of the Eeyou (Cree Nation) of Eeyou Istchee

Administration of Justice

The Circuit Court of Quebec comes to Wemindji only on a periodic basis to hear and administer cases.

Other than a few cases, the Coordinating Judge has suspended, since September 2004, the hearing of

all by-law infractions. This suspension has continued into the entire 2004–2005 court calendar. The

periodic visits and the suspension of certain hearings have led to long delays in the administration of

justice in Wemindji. The rule of law and an efficient administration of justice are essential for the social

well-being of the community and Cree Nation of Wemindji. Consequently, Wemindji recommends the

review of section 18, particularly the implementation of paragraph 18.0.37, of the James Bay and

Northern Quebec Agreement in order to address the present administration of justice. 23

Cree First Nation of Waswanipi

Chief Robert Kitchen, Mr. Allan Happyjack, Executive Director, and Mr. Sam Gull, Director General, of

the Cree First Nation of Waswanipi, made a presentation to the Commission. Chief Kitchen spoke on

the following issues and concerns of the Cree First Nation of Waswanipi:

Resource Development and the Waswanipi Iinuuch

The Waswanipi Iinuuch, as they call themselves, and their historical and traditional territories have been

subject to resource development and its impacts since 1930. The Waswanipi Iinuuch have especially

been impacted over the past fifty (50) years by mining, commercial forestry and hydro-electric

development. The Waswanipi Iinuuch claim that “Waswanipi lands…and its territorial integrity,

sovereignty, jurisdiction, control and management still continue to be subject to damage, exploitation

and over-harvesting by means of trespassing, clear cutting and illegal activities in the absence of a

Comprehensive Agreement for the Waswanipi Iinuuch and the issuance of a proper permit or licence

from the Cree Nation of Waswanipi.” 24 Consequently, the Cree First Nation of Waswanipi “wish to

express its intent, objective and spirit to negotiate a Comprehensive Agreement for its future generations

with the Governments of Canada and Quebec.” 25